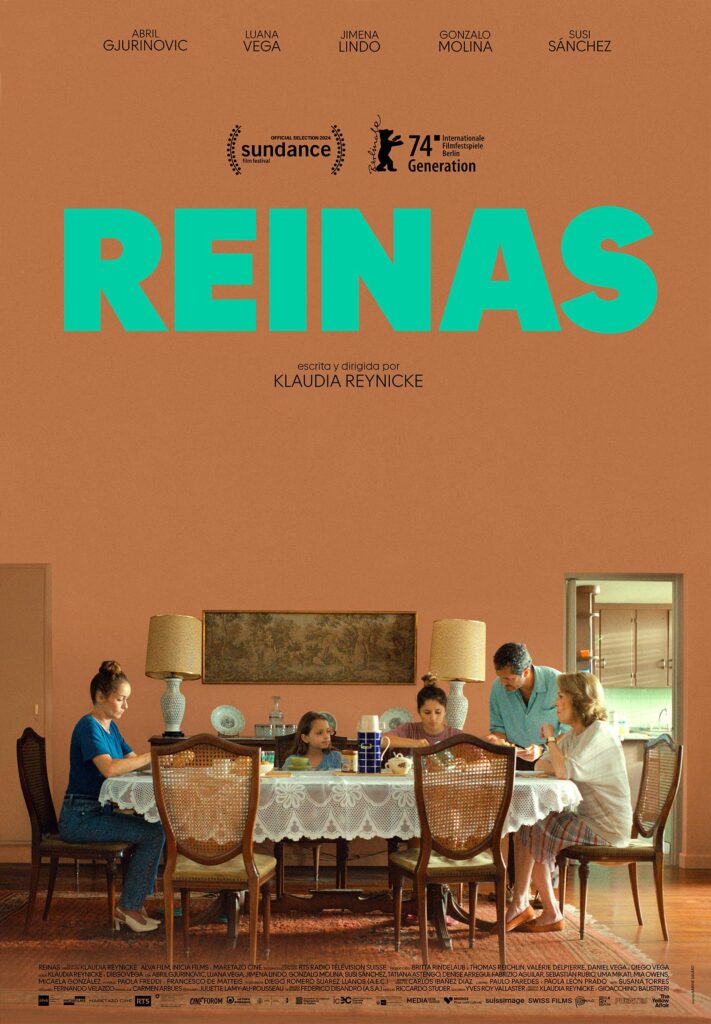

On November 4th I did an interview with Klaudia Reynicke, the Swiss-Peruvian writer and director of the film Reinas, or Queens (2024). Reinas premiered at Sundance Film Festival and is the Swiss entry for the International Feature Film category at this year’s Academy Awards. The film tells the story of two young girls aged 14 and 11 living in Peru amidst the economic crisis and ongoing terrorism happening in the country in the 1980-90s. Their mother Elena gets a job in Minnesota and is planning to leave with her daughters, while their less-responsible, comedic, taxi-driver father Carlos re-enters their life and procrastinates signing the papers necessary for them to leave. I saw Reinas at the Mill Valley Film Festival BAMPFA screening, which was followed by a Q&A with Klaudia. I introduced myself to Klaudia as a Media Studies second year student at UC Berkeley, and told her about the clubs and activities I participate in. Klaudia told me at the start of the interview how, “it’s always amazing to actually be able to talk with students that still, with everything, have the hope and dreams in this crazy career.”

Dahlia: I loved seeing Reinas. It was an amazing film.

Klaudia: Thank you.

I saw it at the Mill Valley Film Festival at BAMPFA, where you did a Q & A after. So I was wondering, what is it like to be able to show Reinas at all of these different film festivals? How has that experience been?

It’s always an amazing thing to have the opportunity to show a film in festivals or with an audience where I can do a Q & A. Most films, especially studio films and things like that, do not have that part. When you create a film, you write it, and then you shoot it, and then it goes into post production, and then it goes out. Normally, that’s it. It’s like giving birth, and then the kid goes to do whatever. But having the opportunity to actually connect with an audience, for me, it’s amazing because it’s the only time that I get to actually have this kind of connection, and get what people are feeling about the film that I would never know. It’s not the same thing as reading reviews or whatever – it’s real people. So it’s always been very warm. And I feel that the more the people connect, the more I did a good job talking about something where everyone can identify. It’s a very important moment for the film, but also for me. I think, because I do these kinds of films – independent author films – I get the chance to also do that, and it’s just an amazing moment.

Yeah, that sounds so nice. I feel like once you put it out there, you want to hear what people are thinking, and see people watching it.

Exactly, and no matter what they think. I mean, I’ve done other films that were more controversial, and it’s always very interesting to actually suddenly get someone who’s outraged, right? As long as the film gets to move some things inside, that’s the interesting part for me. It’s like going to watch art in a gallery or a museum. If you forget about what you saw, that’s horrible, but if you either love it or hate it, that’s when it gets interesting. It means there is something that is actually getting to you, to the audience, to people, and that’s the interesting part.

That’s awesome, thank you. I was wondering, because you’re a writer and a director for Reinas, what was your writing process like?

I mean, it was long, but at the same time, it was on and off because it was such a personal film that I felt I needed to take some time off sometimes to rethink about it. I started by myself for about a year, and then I wanted to actually have someone else on board, because there were some political, social contexts that I couldn’t handle by myself. I was very young when I left Peru, so I called Diego Vega and he co-wrote it with me. It was actually a very nice part of the process, because I had someone to talk with. We had these long talks – he lives in Barcelona, I live in Switzerland, but we had these endless talks, not even particularly about what we were writing, but sometimes about a character and relating to both of our lives. So obviously for Reinas the basics are from my life, but also there’s a lot of Diego in there. Somehow, maybe he would tell me the tale of his dad that did this and did that. And then after a few months we were like, ‘oh, that was funny, let’s put it in there.’ It was a very long process. This kind of process is amazing, and you suffer, and you’re very happy and excited, and then you suffer again, because when you write, you have to be able to create an entire world. And in order to do that, it’s very complicated to actually be able to equilibrate, to balance everything. So sometimes it goes well, and sometimes it doesn’t. I had another project with him that now is frozen because we didn’t find a way to actually continue that one. With Reinas, I guess there was a special passion or feeling that made it possible. But the process is always complicated. For this one, it was like four years on and off, and we both had other other projects in between. I did a series in between, and he did all the writings. And sometimes we wouldn’t work on it for six months or whatever.

That kind of brings me into my next question too. Did you find it especially emotionally challenging to make this film because it was so autobiographical to your own life story or your personal life?

I think yes and no. Somehow, once I had the script, I was able to actually detach from the personal because we created characters, and they started having their own lives. And once I went through casting the actors, they started giving life to those characters that already had their own lives. You really start making the film be the film, and disconnecting from whatever I wanted to say. But obviously, I think the base of having true feelings and knowing about this reality that I went through, which was in there, and maybe because I come from the documentary world, it was always very important for me to have an aspect that felt very real. And that was kind of away from anything that felt fake or that felt theoretical. So I was always pushing to be the most real possible, but it wasn’t hard for me as Klaudia anymore. It was more like, okay, how can I work with this story that used to be mine, it’s not mine anymore, and now it’s gonna be other people’s.

I feel like that realness really came through. The whole time I was very much like – how is this not a true story? In a way, that’s kind of what I was balancing in my head when watching, and especially hearing you talk after, I was like, ‘Oh, wow, that’s why that felt so personal.’ And then also the undertones of terrorism and the dynamics at the time were so subtle – or some things were very subtle – and you could feel it there. I was thinking about the family’s housekeeper and the class differences between the different families. And who could leave [Peru] and who couldn’t leave, those things were a little bit more subtle. But they were there, and they were powerful, so I really appreciated that.

Thank you. Yeah, I think it’s important for a story to actually have different shades and to be able to have characters that are neither black or white, because I get pretty bored with films where you know everything; it’s like the mean one and the good ones – life is not like this. So you know, to make life in each one of these characters, no matter what their weaknesses are or their bravery. I think it’s actually good to compensate, because we are all like this. We all have good and bad parts. So I think we’re able to relate more with characters that are imperfect like us.

Do you have a favorite scene from the movie, or a scene that was the most fun to shoot?

I mean, I don’t know if I have a favorite scene. Obviously, when I get to the end of the film, I still feel emotional I would say but that’s because of the entire film. So, you know, if I wouldn’t have, like, the rest of the film, you know. So that’s something funny, because I’ve seen the film like 10,000 times probably, and I still get emotional at the end, and I still feel for that father, and I still feel for the girls and for that mother. I think a few scenes were, I wouldn’t say fun to shoot, but they were emotional. I remember when [Carlos, the father] has to sign [the papers for the family to leave], on the script, that used to be the last scene actually. We actually flipped the script. When he’s driving the taxi with the girls, which is the last scene, that used to be before that. They were actually going to [sign the papers]. But on the script, it worked really well, and somehow, on film, it didn’t. It just didn’t. It made the film totally dark, because we’re ending with this guy signing and being with the girls, and then you’re like, ‘Oh my god!’ So it just didn’t work.

And I remember shooting that scene, I was obviously very concentrated, because the actor had to be super concentrated, and he was crying, and he was super emotional, and I was so concentrated on having it done that I was there, and I got a bit emotional, but my concentration was stronger. But when I said cut and I detached from the screen, and I looked at everyone, everyone in the crew had cried. And the actor couldn’t stop crying. And I was like, ‘I guess this works.’ And it was too powerful, which is why once we were on the editing, we couldn’t leave the family like this. Me and my editor were like, we need to bring light. We have to flip. We have to flip beyond the scene. We have to make him give them hope, because right now, everyone’s like “Ah, this is horrible!” And you’re the only one who knows it – I’ve never told this, I think, before.

Wow! Oh my goodness, exclusive information! I think you made a good call there, but that’s so interesting. I’m glad that you were able to figure that out, because I can imagine you could have a situation where you’re like, ‘Oh, I’m screwed.’ You know, you’re watching, and you’re like, oh no.

I think the film works. But at some point, the end was – you felt it was heavy. I showed it to my husband. My husband is not in cinema, and he has some distance, right? And I was all excited about showing him that edit. And he’s like, ‘I feel very heavy.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, but, I mean, it’s a drama.’ And he’s like, ‘Yeah, but…’ and I was like, ‘Oh, my God, oh, what do I do.’ With my editor, I started telling her, and she’s like, ‘Yeah, but it’s a drama!’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah, but you know, it’s still weird. We didn’t feel like this in the script.’ And after a few days, I’m like, ‘what if we do this?’ At the beginning, she’s like, ‘No, there’s no way, we need to finish with that theme.’ But suddenly, when I said ‘we need the light,’ she’s like, ‘you’re right, we need to go for the light.’ I mean, this can’t end in darkness.

Do you have any of your own favorite movies or film inspirations?

I do actually. Obviously, I’ve watched many films – it’s funny, because I always tell people I’m not a cinephile. My husband is a cinephile, and he watches everything. He knows all the names. I’m dyslexic, so I don’t remember names. But I do watch films, I don’t consider myself like a cinephile, because I don’t think I watch enough films, but there’s a lot of things there that got me inspired. But I think there are three films, really, that I can say, felt very close when I was writing [Reinas]. And the first one is Roma from Curaon. The second is Y Tu Mama Tambien, which is a coming-of-age of these two kids. And the third is from Heddy Honigmann, who is a documentary filmmaker. She was actually born in Peru, but she ended her life in Amsterdam, and she did this documentary film that’s called Metal Y Melancholia. It’s a film that she shot only in taxis in Peru in ‘91. She actually went to Peru with her camera, and she got into all the taxis, and she’s just like asking them about their lives, to these taxi drivers, and most of them, they have nothing to do with taxi. They’re like lawyers, doctors, because the situation was the one that was in the film. The situation was so bad that everyone became a taxi to survive, right? That film, I watched it so many times, because in order to recreate the world that we see in Reinas, it was an amazing object – the documentary. So that helped a lot. Also with Carlos, Carlos became a taxi because of that film.

That totally correlates. Wow, yeah, thank you. So, as you know I’m currently studying Film and Media Studies. I guess in general, how did you know that film was what you were interested in and what you wanted to pursue? And then, how do you feel that your time as a film student contributed to your experience or your filmmaking now?

Let me answer this second question first, because I think it’s easier. Being a student, I didn’t go straight to film. I actually was an anthropology student, I had a bachelor’s degree, and then I came back to Switzerland, and I got a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree in sociology. So it has nothing to do with film. When I was actually studying anthropology and sociology, I worked in TV to make money as an assistant producer for this documentary filmmaker. Then I came back to Switzerland, and I worked for another filmmaker, and then for a producing company. I used to paint a lot. I used to be a painter, and that and the studies of anthropology and sociology, cinema kind of took from both. So when I decided to go to film school, I was older. I was actually almost in my 30s, and I didn’t want to do a bachelor’s or whatever anymore, because I didn’t have time. I’m like, if I want to do this, you know, I have, like, 10,000 diplomas now! I didn’t know what to do. So I did a master’s degree in filmmaking in Lausanne, which is a city in Switzerland. And I did it for one purpose: to get a network.

I had no idea how to be on a set, how to film. When I was still studying sociology in Lausanne, I went one summer semester to NYU to the School of Arts because one class was documentary filmmaking where they taught you to do everything – to be on the set. So I’m like, ‘Okay, I’m gonna do that class. I’m gonna see if I like it.’ I did it and I liked it. I finished my master’s degree in sociology, and then I’m like, ‘Alright, so I’m gonna apply to do these two years of Master’s in filmmaking so that I connect with people and understand about the network.’ And that’s pretty much why I did it. And it helped a lot – it was much easier for me to understand the basic rules on how to get money, how to talk to producers, how to pitch a project, I had no idea. Also having a diploma in the field does help; to go to producers and pitch your project and be like, ‘blah, blah, blah.’ So, it does help, but you don’t have to do it. I think I truly understood how to make films by being on set. Helping out other people, and then on my own sets that had no freaking idea at the beginning what to do, but you have to survive it. You learn by working. But with the connections, with the network, it’s like, really good to be in a film school. You have time. I was older. You’re still young. You can still do like four professions. You don’t have to choose right now.

I love that. What advice would you give to emerging filmmakers and those in film school today?

To follow their passion. I think in filmmaking, there are no rules. The only rule is that that fire that is new, it is either there or is not there. I don’t think you can actually help anyone become a filmmaker or a writer or a musician or a painter. I think it has to be the drive that comes from the inside. And so if it comes from inside, you have to follow that. So that’s the only thing. I think any advice would be wrong. I think the advice comes really from the drive, from the passion. And when you have that, you’re gonna find ways to actually get what you need in order to make your film. If you want to have an interview with this person, and you get it, that’s one thing. So that’s perfect. You know, you’re just following whatever you need to make whatever you need. You know, follow your passion. And say no to any barriers that are there. Just do it.